Hardware documentation

Camera Sensors

Getting Started

Environmental Specifications

Deployment

Our devices

Filter

RVC generationConnection

Stereo Depth

Field of View

Sensors

RGB Camera Only

Stereo Camera

ToF

Thermal Sensor

GridTable

OAK4 S

Camera

OAK4 D

Camera

OAK4 Pro

Camera

OAK4 Pro W

Camera

OAK-D S2

Camera

OAK-D W

Camera

OAK-D Pro

Camera

OAK-D Pro W

Camera

OAK-D Lite

Camera

OAK-D

Camera

OAK-D S2 PoE

Camera

OAK-D W PoE

Camera

OAK-D Pro PoE

Camera

OAK-D Pro W PoE

Camera

OAK-D PoE

Camera

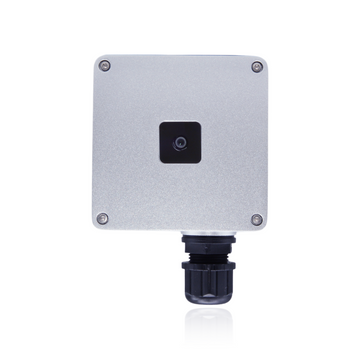

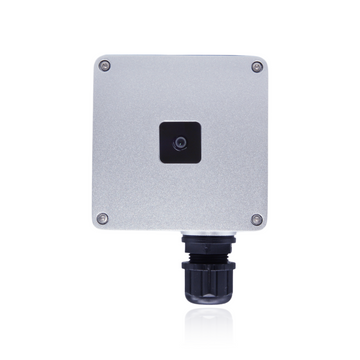

OAK-1 PoE

Camera

OAK-1 W PoE

Camera

OAK-1

Camera

OAK-1 W

Camera

OAK-1 MAX

Camera

OAK-1 Lite

Camera

OAK-1 Lite W

Camera

OAK-D CM4

Camera

OAK-D CM4 PoE

Camera

OAK-D LR

Camera

OAK-D SR

Camera

OAK-D SR PoE

Camera

RAE

Camera

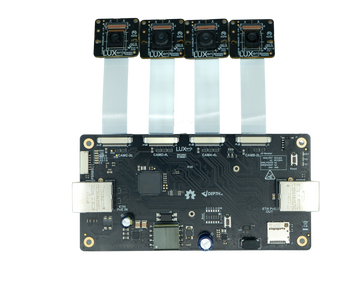

OAK-FFC 4P PoE

FFC Board

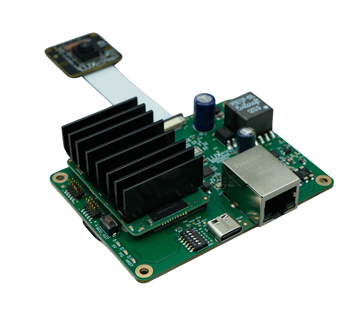

OAK-FFC 1P PoE

FFC Board

OAK-FFC 4P

FFC Board

OAK-FFC 3P

FFC Board

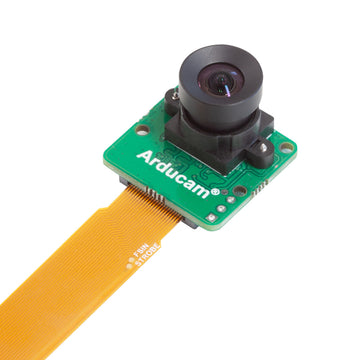

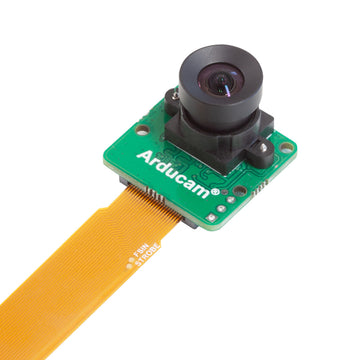

OAK-FFC AR0234 M12

FFC Module

OAK-FFC IMX462

FFC Module

OAK-FFC IMX477 M12

FFC Module

OAK-FFC IMX577 M12

FFC Module

OAK-FFC OV9282 M12 (22 pin)

FFC Module

OAK-FFC OV9782 M12 (22 pin)

FFC Module

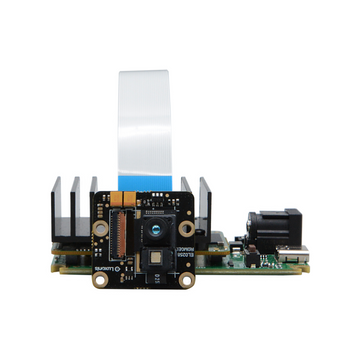

OAK-FFC ToF 33D

FFC Module

OAK-FFC IMX582

FFC Module

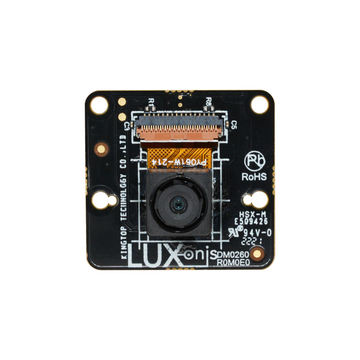

OAK-FFC-IMX214-W

FFC Module

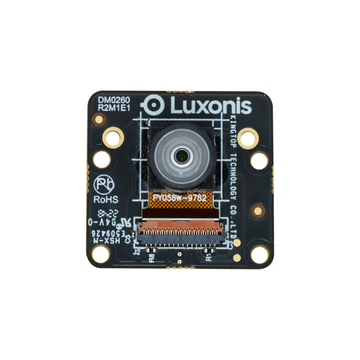

OAK-FFC-IMX378

FFC Module

OAK-FFC-IMX378-FF

FFC Module

OAK-FFC-IMX378-W

FFC Module

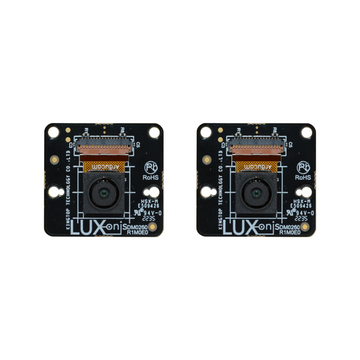

OAK-FFC-OV9282

FFC Module

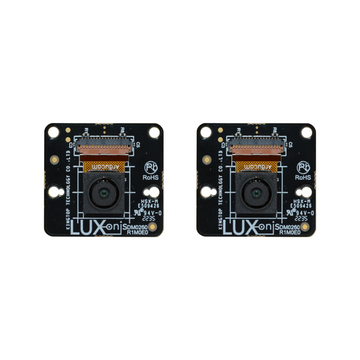

OAK-FFC-OV9282-2

FFC Module

OAK-FFC-OV9282-W

FFC Module

OAK-FFC-OV9782-FF

FFC Module

OAK-FFC-OV9782-W

FFC Module

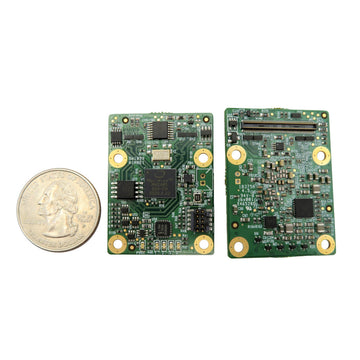

OAK-SoM (sets)

SoM

OAK Thermal

Camera

Y-Adapter

Other

FSYNC Y-Adapter

Other